Q&A:: What would California’s proposed single-payer healthcare system mean for me?

California and New York become the latest states to consider single-payer health insurance systems as Congressional Republicans prioritize repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act.

The prospect of a universal single-payer healthcare system in California — in which the state covers all residents’ healthcare costs — has enthralled liberal activists, exasperated business interests and upended the political landscape in the state Capitol. But some are still trying to sort out what exactly all the fuss is about.

Let’s start with some caveats. This proposal faces a steep climb before it becomes a reality. It almost certainly will require new taxes to finance it and that would entail the major lift of cobbling together a supermajority of votes in both houses of the Legislature for approval. Even if that happens, it still faces another hurdle: Gov. Jerry Brown, who has been publicly chilly toward the idea. Voters would also need to OK the proposal to exempt it from spending limits and budget formulas in the state constitution. And there’s yet another big obstacle: getting approval from the federal government to repurpose Medicare and Medicaid dollars.

Still, single-payer has emerged as a litmus test for California Democrats. The proposal, by state Sens. Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens) and Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) is still evolving, but here’s what we know so far about the bill and how it would work:

What is single payer? Is it the same thing as a “public option?”

- Under a single-payer plan, the government replaces private insurance companies, paying doctors and hospitals for healthcare.

- That’s different than a public option, in which the government offers an alternative to other insurance plans on the market.

It’s all in the name: In a single-payer system, one entity — in this case, the state of California — covers all the costs for its residents’ healthcare. Effectively, the government would step into the role that insurance companies play now, paying for all medically necessary care.

A number of countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom, have single-payer models. While there have been calls for a similar system in the United States for decades, the cause was energized by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, which backed a “Medicare for all” healthcare system, modeled on the existing program for Americans aged 65 and older.

Other efforts to enact state-level single-payer systems have fallen flat. A 2011 program in Vermont was abandoned three years later due to financing concerns. Last year, voters in Colorado rejected a ballot initiative to create such a program.

The California bill bears the imprints of Sanders’ campaign — and of the California Nurses Assn., which has long pressed for a single-payer plan. It has become a rallying cry for the progressive flank of the Democratic party.

“The model here is not the United Kingdom or Canada,” said Darius Lakdawalla, a health economist at University of Southern California. “The model here is Medicare.”

The proposal is different than a “public option,” in which the government subsidizes an insurance plan that competes with private insurers. A public option was debated in the run-up to passage of the Affordable Care Act, but ultimately not included. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi recently returned to the concept, telling California Democrats at their convention in May, “I believe California can lead the way for America by creating a strong public option.”

Gerald Kominski, a professor of health policy at UCLA, said a public option would offer a backstop in states where insurers have dropped out of the Obamacare marketplace. Covered California, the state’s marketplace, is generally seen as robust compared to other states.

“Sure, there’s room for a public option in California,” Kominski said, “but I’m not convinced there’s an overwhelming need.”

How would this change how I get healthcare?

- No more coverage through work or through federal public programs — it would all be in one state-subsidized plan.

- Virtually all healthcare costs would be covered.

Whether you’re insured through an employer, through Covered California or on public programs such as Medi-Cal, as long as you’ve established California residency — regardless of legal immigration status — you would be enrolled in a single plan, which the bill’s backers call the “Healthy California” plan. That would eliminate the need for employer-provided plans and other commercial options.

Michael Lighty, policy director for the California Nurses Assn., put it bluntly: “You’ll never have to deal with an insurance company again.”

Benefits would be generous, including all inpatient and outpatient care, dental and vision care, mental health and substance abuse treatment, and prescription drugs. Patients would be able to see any healthcare provider of their choosing.

Single-payer healthcare could cost $400 billion to implement in California »

I’m on Medicare. What would this mean for me?

- Federal programs like Medicare and Medi-Cal would be merged into the single-payer plan.

- But there’s no guarantee the Trump administration would approve such a change.

Older Californians on Medicare would also be wrapped into this plan. The plan envisions using all the existing federal dollars going toward Medicare and Medi-Cal beneficiaries in California in the state’s single-payer model.

But there’s a hitch: The federal government — a frequent punching bag for California Democrats at the moment — would need to grant a waiver to redirect that money.

“The question is: Will the Trump administration approve such a waiver?” Kominski said.

In one sense, he said, the request could align with conservative ideology that calls for increased power of states relative to the federal government.

“On the other hand, for political purposes, I can see the Trump administration saying there’s no way we can sign a waiver,” Kominski added.

Supporters say they believe they can obtain a waiver, but have gotten no indication from the Trump administration that they’d be inclined to sign it. It is unclear what would happen if they cannot get federal approval.

This is a sea change in the way healthcare would be organized in California.

— Darius Lakdawalla, professor of economics, University of Southern California

Would this affect how much I spend on healthcare?

- No more co-pays, premiums or deductibles

- But Californians would be hit with higher taxes

At this point, it’s hard to say. The existing language of the proposal does away with a lot of the financial burdens associated with the current healthcare system, such as premiums, deductibles and co-pays.

“When [patients] go to a provider, they won’t have to pay anything,” Lighty said. “They won’t get a bill from the insurance company after surgery. They won’t be told to pay thousands of dollars to get into an ambulance. All of that goes away.”

Average premiums for Californians who get insurance through an employer (as the majority of people in the state do) were just under $600 per month in 2016, according to the California Health Care Foundation — higher than the national average.

But the new system would not eliminate those costs entirely.

“If you’re paying for health insurance right now through healthcare premiums and cost-sharing, you’d end up paying instead through taxes,” said Micah Weinberg, president of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. “There are some people who at the end of the day will end up paying more, others who will end up paying less.”

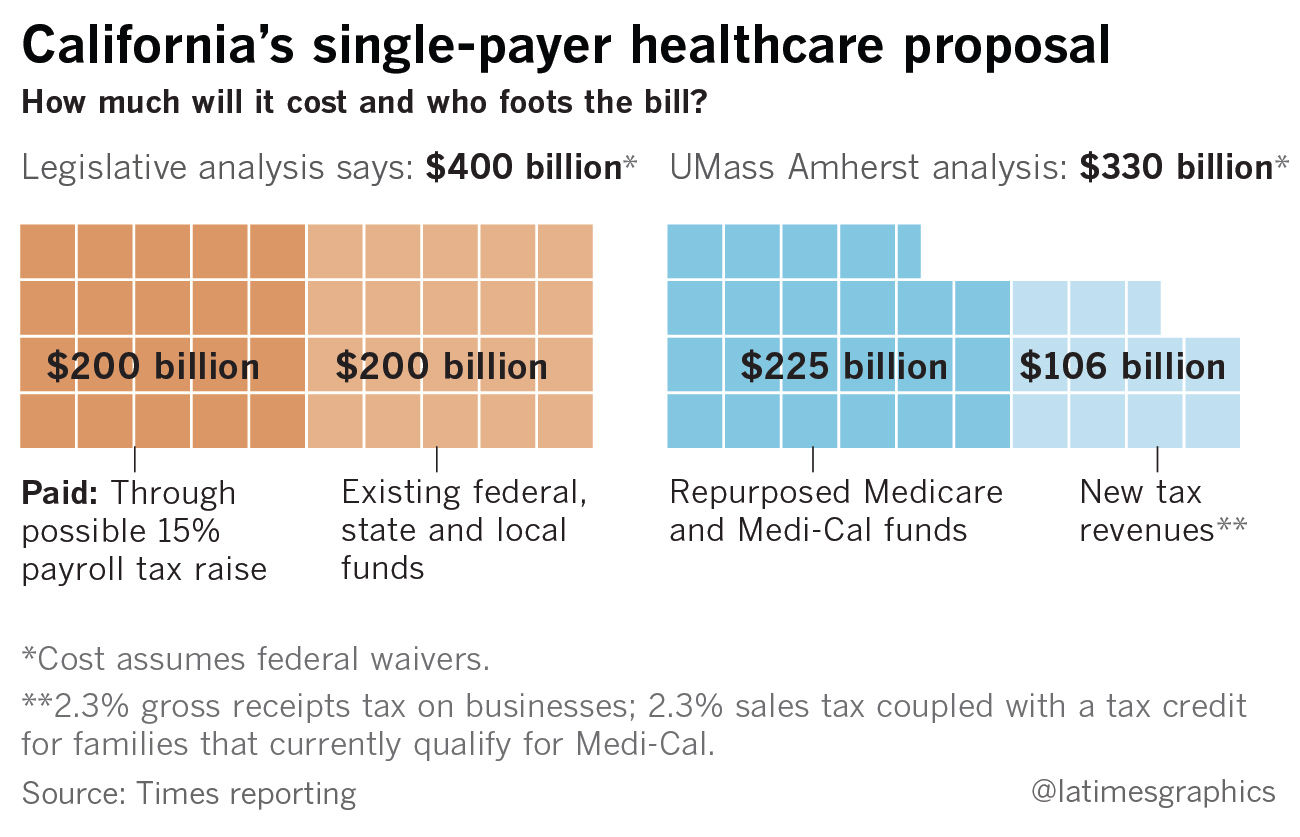

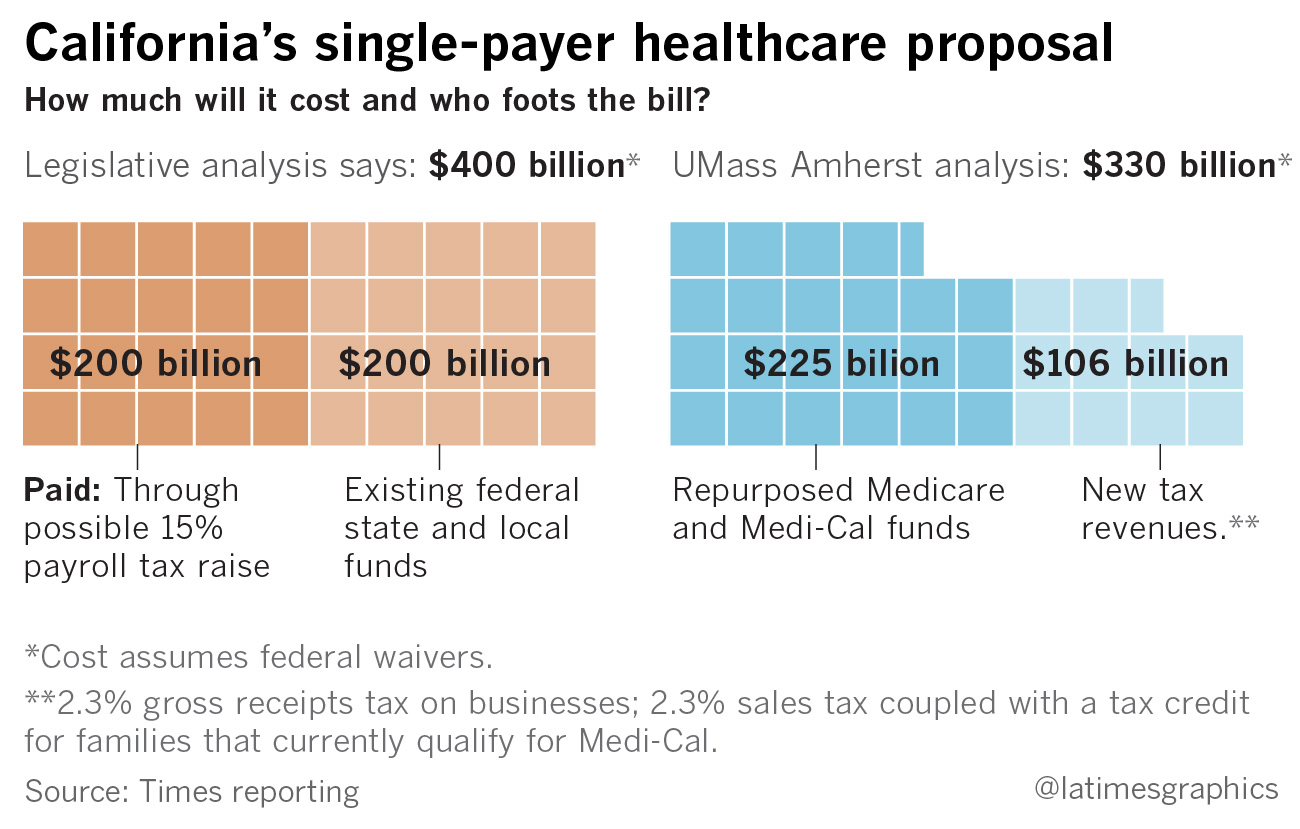

A recent state Senate analysis pondered a 15% payroll tax as a way to raise the estimated $200 billion needed in revenue to cover the program’s costs. The analysis assumes another $200 billion would come from existing federal, state and local funds.

The nurses’ union paid for their own study of the proposal, conducted by economics professors at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Assuming federal waivers, the analysis suggests $225 billion could come from repurposed Medicare and Medi-Cal funds.

An additional $106 billion would have to come through new revenue. The study suggests two new taxes: a 2.3% gross receipts tax on businesses and a 2.3% sales tax coupled with a tax credit for families that currently qualify for Medi-Cal.

These ideas are all possible scenarios to generate new revenue, but the bill currently does not contain any specific tax provisions.

“It's not free healthcare. That's something people really need to understand,” Weinberg said. The key question, he added, is “do you pay the government or do you pay a private insurer?”

What about overall healthcare costs for the state?

- A legislative analysis estimated overall costs would be $400 billion per year.

- Proponents of the plan are touting savings from the single-payer system and have come up with a lower annual price tag: $330 billion.

The Senate analysis pegged the total cost for the plan at $400 billion per year. Half of that would come from existing money, the other half from new revenues such as a payroll tax. Because the plan would eliminate the need for California employers to spend money on their workers’ healthcare (an estimated $100 billion to $150 billion annually), the total new spending on healthcare shouldered by the state under the bill would range from $50 billion to $100 billion yearly.

The $400-billion price tag is more or less in line with what Kominski and other researchers at UCLA estimated was the total healthcare spending in California in 2016: around $370 billion. Around 70% of those expenditures were paid by taxpayer dollars, the study found.

The UMass Amherst analysis, commissioned by the nurses, suggested that a single-payer system would decrease overall healthcare spending in the state by 18%, thanks to streamlined administration and the possibility of negotiating for reduced prescription drug prices. The total annual tab, according to the study, would be around $330 billion.

Both estimates far exceed the $183 billion in total spending in next year’s state budget as proposed by Gov. Jerry Brown.

The measure would establish a Healthy California board, appointed by the governor and the Legislature, that would set rates on how procedures would be reimbursed and negotiate with providers.

An important question is how the system would pay for care. The Senate analysis says the bill as written would follow a “fee-for-service” model, in which doctors and hospitals would be paid based on the number of procedures or patient visits they bill for.

Such a model has been criticized for driving up costs since it gives an incentive for doctors to provide more — but not necessarily more effective — care. Over the last few decades, the healthcare industry has moved toward different payment models that are meant to encourage efficiency and better care coordination.

Health economists say a system where doctors and hospitals are paid on a fee-for-service basis, and patients have no cost restraints from premiums or co-pays, means it’s more likely that patients will seek more care.

The measure’s backers dispute the legislative analysis’ stance that the model would be purely fee-for-service. Their commissioned study said that alternate payment methods to hospitals and reduced pharmaceutical costs through a formulary or price controls could rein in overuse of care.

There are other unknown costs, and they could be substantial. The analysis, for example, notes that the development of information technology systems to administer such a program could cost billions.

“Anybody who says they know how much this program is going to end up costing is rather optimistic,” Lakdawalla said. “This is a sea change in the way healthcare would be organized in California.

I work in the healthcare industry. How would this affect my job?

- There may be more time for patients instead of dealing with billing for doctors, but it could also affect their paycheck.

- Those who work at insurance companies or other administrative posts may lose their jobs.

For healthcare providers such as doctors and nurses, single-payer supporters say the proposed system would mean more time treating patients and less time navigating the complex world of insurance preauthorizations and reimbursements.

“Doctors would no longer have to deal with...hundreds of payers,” Lighty said. “You now have a single payer who will pay reliably or swiftly.”

Depending on how the program decides to reimburse for care, that could affect how much providers get paid. Lighty said the program would likely use the same rates as Medicare, which is less than what commercial insurers pay but more than Medi-Cal.

“Imagine what will happen if physician reimbursements fell by 15 to 20%, and those same reimbursements did not fall in Washington, Oregon, Arizona — [states that] are not implementing single-payer,” Lakdawalla said. “What happens to the population of doctors practicing in California?”

There’d be more upheaval for those who work in the insurance industry. Since the program would virtually eliminate the role of private insurance in the state’s healthcare market, the Senate analysis predicts that those workers “and many individuals who provide administrative support to providers would lose their jobs.”

The bill would authorize job retraining programs for workers affected by the change.

ALSO

Single-payer healthcare is popular with Californians — unless it raises their taxes

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.