Serious infections tied to medical scopes go far beyond issues with a single device

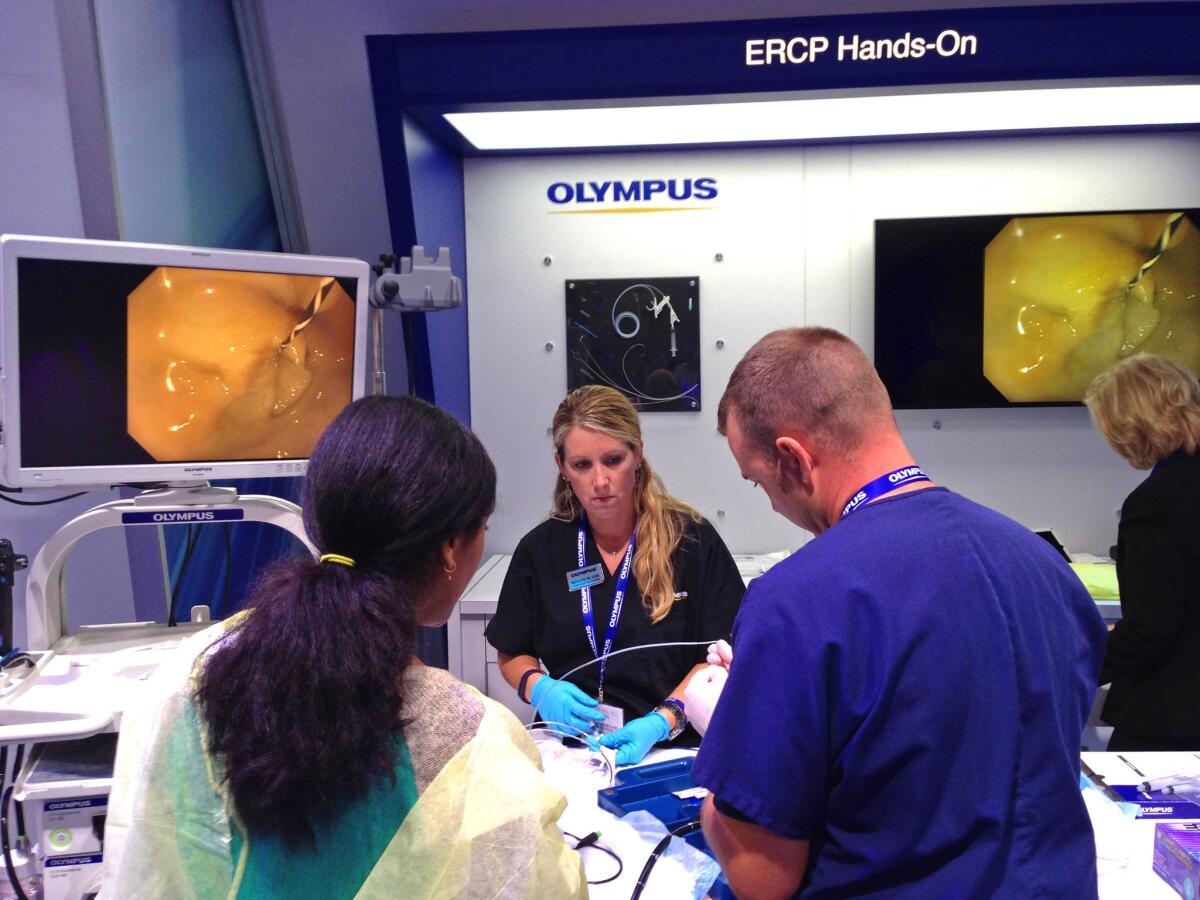

A hands-on demonstration of medical equipment, including a medical scope, at the Digestive Disease Week conference in May 2015. Three recent outbreaks are among dozens of injury reports in a federal database that detail the risk of serious infection from contaminated scopes.

A doctor reported in December that a medical scope commonly used to examine patients’ lungs had infected 14 people with a superbug that kills half its victims.

Yet another type of scope, used to see inside the bladder, sickened three patients with a different bacteria in March, according to a nurse. The device was sent to the manufacturer, which found “foreign substances” inside despite cleaning.

And in November, a nurse manager reported that seven patients were infected with an often lethal bacteria known as clostridium difficile from a device used for colonoscopies.

The three outbreaks are among dozens of injury reports in a federal database that detail how the risk of serious infection from contaminated scopes is far broader than a specialized device that recently sickened patients at UCLA, including three who died.

Regulators have blamed the intricate design of that device — a duodenoscope — for being especially hard to clean.

But in the last three years, patients have also been exposed to bacteria — and to human tissue and dried blood — left inside a variety of scopes commonly used to examine the lungs, the colon, the bladder and the stomach, according to the reports.

Infection experts have been warning for years in speeches and research papers that many types of endoscopes can remain dirty after cleaning — only to have their concerns mostly ignored by doctors performing the procedures.

Last year, Cori Ofstead, a Minneapolis epidemiologist and consultant, warned a national group of infection control professionals that she and her colleagues were finding scopes that were still contaminated after they were disinfected according to guidelines.

“This is deeply disturbing to us,” Ofstead told the crowd.

Another researcher, Michelle Alfa, a professor at the University of Manitoba, tested scopes that had been cleaned at a Canadian hospital for traces of blood and protein. She found that 9% of gastroscopes, 7% of colonoscopes and 4% of bronchoscopes still had traces of potentially infectious material.

“We’ve had this issue for a long time,” Alfa said.

Federal regulators say they don’t know how many patients have been sickened by the scopes, which as a group are used tens of millions of times each year.

There are no numbers to quantify the risk because few of the scope-caused infections get reported. The government’s injury reporting system, which keeps names of hospitals and clinics secret, is mostly voluntary.

The cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration show a repeated story: The scope transferred bacteria among patients even though medical staff believed it had been disinfected.

And in many cases, multiple patients were sickened before doctors recognized that the scope harbored bacteria inside its long narrow channel or delicate mechanisms.

“You can’t see inside the scope to determine whether you really did get it clean,” Alfa said.

As the scopes snake through a patient’s throat, intestine and other cavities, they are contaminated with mucus, blood and millions of microbes. But the delicate devices can’t be sterilized like a surgeon’s knife because intense heat would destroy them.

Instead the scopes are brushed, washed with disinfectants, rinsed and dried according to manufacturers’ instructions, a process performed by low-paid technicians that may require a hundred steps.

Mistakes by a hospital’s cleaning staff can go unnoticed for months.

In 2010, the Palomar Health system in San Diego County notified 3,400 patients that they may have been exposed to tainted scopes after workers continued for months to use a disinfectant that was past its expiration date.

Scope manufacturers have said they often find that hospitals reporting infections did not properly clean or maintain the device.

For example, Olympus told the FDA that the bronchoscope that had potentially infected 14 patients with CRE, or carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae, in December had been sent to an unregulated company for repair.

That case was the third reported outbreak suspected to be caused by an Olympus bronchoscope in less than three weeks. In one of those outbreaks, a nurse reported that three people were sickened by another often deadly bacteria.

An Olympus spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

Even when the recommended disinfection guidelines are followed correctly, it’s sometimes not enough. Alfa said that biofilms, a slimy layer of bacteria and yeast, can form inside the scopes, making them extremely hard to clean.

Only after the UCLA outbreak was revealed in February did the FDA take action. In March, the agency began requiring manufacturers asking for regulatory approval of a new scope to provide studies proving that it can be disinfected.

The agency had proposed the rules four years ago, but did not approve them until news of the deadly Los Angeles outbreak raised public concerns.

The new rules don’t apply to devices already on the market. That means hospitals will continue to use current scopes for years.

The rules also do not cover cystoscopes, used to examine the bladder, and gastroscopes, used to look inside the stomach. According to the FDA’s injury database, those devices have also been found to be dirty after cleaning.

Jennifer Dooren, an FDA spokeswoman, said the agency believes the scopes currently on the market are safe.

“The risk of acquiring an infection from an inadequately reprocessed medical device is relatively low given the large number of such devices in use,” Dooren said.

She said it took the agency four years to finalize the rules because it had received hundreds of comments on the proposal, including some raising key scientific issues. She noted the agency had warned hospitals about improperly cleaned scopes in 2009.

The FDA is continuing to monitor reports of scope-related infections, Dooren said, to see if it should do more.

In May, some members of an expert panel created to advise the FDA on improving the safety of duodenoscopes expressed alarm about the even broader danger from the other types of scopes.

“Let’s not just pretend it’s only happening with one set of complex scopes because it is not,” said panel member Phyllis Della-Latta, a clinical pathology professor at Columbia University.

Twitter: @melodypetersen

ALSO:

Hillary Clinton makes a big ad buy targeting voters -- and maybe Joe Biden

Girl, 16, dies of wounds suffered in attack on Jerusalem gay pride parade

Immigrants object to growing use of ankle monitors after detention