A nursing home worker in New Jersey cut a deal for gowns in a parking lot. A clinic director in Florida awaited midnight deliveries of tens of thousands of masks. A South Carolina cardiologist tried to buy ingredients from Lithuania to mix his own hand sanitizer.

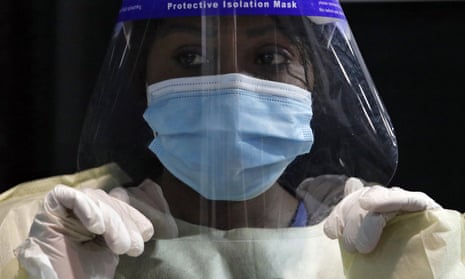

Medical shortages in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, have left many healthcare workers in a desperate hunt for medical supplies. Community clinics, nursing homes and independent doctors, in particular, find themselves on the fringe of the supply chain for masks, gowns, gloves and ventilators. Desperate administrators wire money to offshore banks to acquire supplies.

Most medical supplies – from isolation gowns to the filtration components of N95 masks – originate in China in factories that manufacture so-called spunbond polypropylene out of toxic chemicals. Decades of honing has turned the supply chain into an efficient wonder of globalization. But that crumbled in the face of the pandemic.

“You had all these brokers entering the market looking for arbitrage,” said Michael Alkire, president of Premier, a company that negotiates supply contracts for hospitals. “Unless you were a significant player, it was hard to get access.”

That’s how Carol Silver Elliott, president of the Jewish Home Family, a nursing home in Rockleigh, New Jersey, ended up wiring a man she knows only as “the parking lot guy” a “significant” amount of money for protective equipment for her staff. “I swear I don’t know his name,” she said.

As the crisis dissipates at major hospitals in cities like New York, Seattle and Detroit, the collateral damage is becoming apparent elsewhere.

The burden of managing the disease long-term is shifting to nursing homes, safety-net clinics and outpatient medical practices. As these facilities brace for waves of new infections, they are hustling to stock up on masks, gowns, testing kits, even disinfectant wipes.

It’s not going well.

The first time Andy Behrman pulled up to the warehouse in Ocala, Florida, it was empty.

Behrman, director of the Florida Association of Community Health Centers, had spent early April trying to get gowns, gloves and masks for community clinics across the state.

He ventured into dark corners of the internet to identify distributors, spent hours on the phone vetting vendors, traveled to Tallahassee for a six-figure bank draft, rented a warehouse and loading trucks, and then hired staff for the three-day distribution operation. Sourcing has “basically come down to a huge dose of ‘God, I hope these guys are legit’”, Behrman said.

His first order was delayed for hours, then days. He was promised 100,000 masks, then 50,000. He was guaranteed N95s, which were subsequently downgraded to lower-quality KN95s. All the while, the bill remained the same: $180,000. After another delay and a request for secure bank credentials, Behrman said he was so nervous it gave him chest pains. He called off the deal.

Nearly a week later, on 24 April, a different vendor drove masks overnight from Duluth, Georgia. Nonetheless, in the time since, Behrman has relied on bulk donations of equipment from organizations like Direct Relief, a provider of humanitarian aid, and the philanthropic arms of companies like Centene, a health insurer. He’s still hunting for gowns and gloves. To get a leg up in negotiations, he’s been teaching himself basic phrases in Chinese.

International Community Health Services (ICHS), a nonprofit health center in Seattle, depends on LabCorp nasal swabs for testing but recently has been receiving oral swabs instead. To alleviate shortages, the organization “had to get extremely creative,” said Rachel Koh, chief operating officer. They tried, unsuccessfully, to import equipment from Hungary, Koh said. In the end, a local businessman connected them with a distributor in Hong Kong.

“We are always on the hunt for new suppliers,” Koh said, “but you have to be brave, because you don’t know [who] you can trust any more.”

Independent doctors have grappled with these challenges, too. After months of looking for supplies for his two private practices, Ian Smith, a cardiologist in South Carolina, sought to import supplies directly – learning a bit of Lithuanian in the process – to no avail. So he’s taken to ordering products like ethyl alcohol, aloe vera and storage vessels from Amazon and Etsy to mix his own hand sanitizer.

Paula Muto, a general surgeon in Massachusetts, has struggled to find lidocaine and saline – critical operating room supplies. “All the doctors are competing with each other to get this stuff,” she said.

Muto anticipates that when hospitals resume elective procedures, “all the supplies you can’t buy at Staples” may go on back order. She predicted this could include almost everything except hand sanitizer and disinfectant wipes – assuming she can find those on shelves.

But she has a back-up plan. A distributor she knows in Alabama sources supplies from Spain and other European countries.

“We’re already stocking up,” she said. “We’re trying to make sure we’re at the top of every distributor’s list.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) and along with Policy Analysis and Polling is one of the three major operating programs of KFF. KFF is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.